33 Argentine writers respond to Rolando Revagliatti

Norbert Barleand

By the way, I have experienced many ridiculous situations, some to comment on, others, perhaps, not. Many years ago I attended a book presentation; at the table, the author, the guest to refer to the work and the coordinator of the cycle within which the presentation of the book would take place.

To my surprise, the sharp, sharp criticism of the presenter, almost as if he did not like the book (which would not be an attitude to censor as long as it can be taken as intellectual honesty), generated discomfort.

Reflections: the custom of flattery, praise, a certain ease in interpretation, leads to paths that (sometimes) we are not used to traveling. That was a different event. I must point out that the presenter made a high assessment, with solid argumentation and in an eloquent way, of the author, but not of the book he was presenting; beyond the situation that he generated at the time, there was an opening towards a different space where criticism can be a severe judgment, not always favorable, to attend and consider.

Paulina Juzko

The night my dog kicked me out of the house:

I was returning from an agape after two in the morning. The taxi dropped me off, tired and sleepy, at my suburban home. I opened the gate without inconvenience, but when I tried to do it with the door of the house, no matter how hard I manipulated the key, it was impossible. The key turned normally but the door would not open! He resisted my pushes and my swearing. To do…? My neighbors were in their second sleep judging by the lights out. Who to turn to at such hours...?

Then I remembered Germán, an apprentice owl, who used to spend the night composing and making music. And that he lived three blocks from my house. That's where I headed; luckily the streets of Villa Elisa are a desert after midnight. After much ringing of the bell-caller I managed to get Germán to come out, alarmed to see me and imagining who knows what misfortunes. The idea was that he would accompany me and try to open my door using brute force.

However, despite his good will, despite the efforts he made with his shoulder (shoves) and legs (kicks), the door remained closed: visage de bois.

"It's evident that the security latch on the inside is closed," Germán said.

"How is it possible," I said, "if there is no one in the house?" Or has someone got in with a key?

Just in case we insist on the bell. The dog barked, but nothing more. Eureka! Then, finally, I understood what had happened: they rang the doorbell, Bubú was desperate to get out, she stood on two legs and with her front ones she scratched the door at the height of the latch, so she unintentionally ran it.

Germán dissuaded me from calling a locksmith, he suggested that I sleep in his house the rest of the night and decide what to do the next morning, with a fresh head. We discussed it with Cecilia —Germán's wife— and we made an action plan: my neighbors had a bricklayer working on a construction adjoining my back garden; I would ask that man to climb onto the roof of my shed and then go down to the garden, creep in through the bedroom window-door (which I always left something up in case Bubú needed to get out) and unlock the latch.

And that was how —thanks to the good vibes of that providential mason— I was able to rejoin my penates. What an adventure! And the dog…? Not the slightest feeling of guilt, the whippet. "You'd wag your tail if you had one, eh, crapulona?", I apostrophized her, gently twisting one of her ears.

Marcelo DiMarco

This anecdote that I starred in about twenty years ago serves to remind us that the context rules. Shortly after the appearance of the first editions of Dare to Write and Dare to Correct, the Department of Literature for Children and Young People of Sudamericana invited Nomi and me to give a talk in the mythical building of Humberto Primo —today renovated and converted into the headquarters of Penguin Random House. The talk that my wife and co-author and I had to give was aimed at teachers, potential users, in their classrooms, of those two books of ours. Gigliola Zecchin, better known as Canela, creator of the aforementioned department, was introducing us to the teachers, as they arrived at the room.

"She's a gardener," she commented, referring to one of the participants, and my imbecile response was immediate:

-How good! A few years ago I saw a sign behind the counter of a nursery that said: “If you want to be happy for a week, get married. If you want to be happy all your life, become a gardener”.

"She's a kindergarten teacher," Canela clarified indulgently.

—Oh.

Haide Daiban

A few years ago, three friendly couples agreed to travel together from Buenos Aires to Morocco. The next idea was not to miss the proximity of Spain, to cross to some picturesque place in the south and so we chose Torremolinos.

After the first tour of picturesque and mysterious Morocco, we passed with the ferry to Spain and sighted the Rock of Gibraltar. And already in Torremolinos we showed up at the hotel under a good European rain. Since it was midnight, there was no open kitchen and our appetite was fierce, they recommended a nearby bar, in front of a beautiful neighborhood square. The friendly and talkative owner of the bar was accompanying two drinking patrons, already tipsy, leaning on the bar.

Glass bells covered various dishes that, he assured us, were homemade. "Come in, man, my lady cooked for you!" He arranged three tables and began by bringing olives, I think from La Rioja, large and fleshy.

"They're good," he said and without further ado he put his hand in, ate one or two, as if to give us courage and we smiled at each other for the audacity. Then he brought the wine and poured himself a glass, "it's good, drink up." While he was heating up the orders of rice, chickpeas and meat, he told us what happened to him that week, the visit to his mother's house, an older and brave woman, he said, for having climbed on a chair that he placed on a table, from where he He started painting the ceiling of his living room. “Mother!”, she told him, “what are you doing, you will kill yourself”, and at that moment he rushed out to fetch a plate. When my husband demanded his food, he replied, “it will come, when the device goes beep! I will bring it to you". The appliance was the microwave. He indeed he did peiiiiii! And we ate almost in shifts.

Outside the rain was torrential, the owner said that he would turn off the television so that it would not disturb the conversation and took his “remote control”, as he called it, and that it was, in fact, a broomstick. He pressed from below and turned off the hanging TV. That joke, logically, caused laughter.

The men at the bar argued a bit and the older one made to leave, slipped on a sodden cardboard at the entrance, fell dramatically on his back and one of our friends, a doctor, saw him pale and rigid and thought of an emergency. "Call the ambulance," he asked the owner; He came out the door and started yelling “Ambulance, ambulance!”

After twelve o'clock at night, without pedestrians, far from the ambulance station, we were terrified and amused, the ambulance was not going to arrive. And at that moment the injured man reacted and said to his companion: “Did you think I had gone”, and he moved his arm up, “no, you will put up with me a little longer”.

We applauded, happy, and the man approached the table and in gratitude for our intervention, he recited a poem by Antonio Machado (he announced it as if the title were "The Lawyer"). I must say that he moved us, the theme and his voice. Next, he began to sing a complete tango, we looked at each other, no one remembered all the lyrics.

Our doctor friend charged up and picked up dessert orders, opened the ice cream box on his own and began to fly the ice creams over each one of us, we stopped them in the air and between laughs we paid for the dinner with a show, which turned out to be the most cheap.

On the way to the hotel, our hubbub woke up the sleeping Torremolinos. Despite the passage of time, we do not forget the reciter and much less the smiling owner of the bar.

Fernando G. Toledo

Not because there are few, but because there are so many, I don't remember any in particular. Now the following is presented to me: after some indiscipline in secondary school, the preceptor and her worst side told me: "Tomorrow, if you don't come with your mother, you won't go to school." I replied, to change her face: "My mom is in heaven." I waited for her face to change and when she was going to say something I turned around and completed her: “she is a stewardess”. In spite of everything, she must have thought her joke was good, because she didn't ask me for my parents' company again to continue at school.

Irma Verolin

Autumn 1992. I had returned from India where I had spent three months and lived amazing experiences, materializations, synchronic connections, healings, oral testimonies of unusual mystical experiences from people from all over the world, let's say that I had a head tuned to another reality. As soon as I arrived in Buenos Aires I found the book published for preteens that I co-authored with Olga Monkman. The publisher immediately sent me to carry out the diffusion to Bahía Blanca. At that time, people traveled to India via Europe, so it took three days between connecting flights and waiting at airports. I barely managed to sleep at times. This added to the time changes, to the excessive attention that must be had in Indian airports where sometimes not even English is spoken but in local dialects, which added more tiredness to my tiredness. I must admit that ever since I left the ashram in South India I have been in a daze. At the publisher they gave me money and tickets. I walked a few blocks down an avenue and a supposed family in a car spoke to me from the other side of the window. They told me that they were going to make me increase my money. As I came from a magical space, without having too much awareness, I followed the dialogue. Suddenly everything darkens or whitens, I don't remember well, between the dialogue and what happened afterwards I have no records. I only know that I stood in the middle of the street yelling: “They robbed me!” Due to the impact I remained sitting on the curb of the sidewalk, and I dedicated myself to crying profusely. Adolfo, my friend, told me that I was the only person who put his money in the hands of thieves and then talked about magical phenomena. I read something about psychic thefts, but the truth is, I don't really know what happened. Result: I replaced the money and left for Bahía Blanca. At sunset I had to carry out the workshops. There were a total of one hundred and fifty teachers and school directors. So they were divided into two groups and the workshops to be coordinated were two on the same day, one after the other. They placed me behind a desk, with my elbows propped up I began to speak. Then I find myself with my head buried in my arms, someone touches my shoulder, says: "Are you okay?" Apparently in the middle of my talk I fell asleep completely, it seems that the teachers remained in suspense, waiting, then they thought I had fainted or something worse. I did the second part standing up so as not to succumb to sleep, a product of jet lag from my recent trip.

The book sold well, I directed the teachers to use it as a literary production workshop. A few months later, on the corner where my money was stolen, I found the exact amount that had been stolen lying on the sidewalk. I swear it was the same amount and in the same corner: evidently the magic continued. And it continues to this day.

Daniel Arias

The year was 1978, in the midst of the Military Process, El Círculo de los Poetas had already been dissolved as a poetic cultural organization, and many of us moved away like a cabotage big bang: we stopped seeing each other almost every day to meet from time to time. when in some rock or in the halls of the Meridiana Gallery or in the Casona de Iván Grondona, but with some we continue the journey together chasing dreams. Such is the case of my poet friend Daniel Cejas, now disappeared, with whom I shared an unusual experience.

Daniel learns that literary poetry workshops had been organized at the Argentina de Escritores. At that time my wife, Beatriz Arias, was a mother for the second time, and with the small children we couldn't do much; therefore, the one chosen to find out was me. I combined with Daniel Cejas and we went to Sade Central, on Uruguay street. They tell us that the class for that day had already started and we jumped at the chance to enter it. We tapped lightly on the tall door and slowly opened it, walked through, closed it, and stood very still. Facing the entrance door, sitting behind a desk was a tall, bald-headed man with blue eyes, surrounded by tables and chairs with twenty or thirty workshop participants. We interrupted without saying a single word and the silence was immense. Everyone turned to see who entered.

The man gets up, he too without saying a single syllable, and resolutely approaches us and asks us: “What do you want here!?”, and his eyes nailed us against the wall. He immediately pulled a silver revolver out of his jacket pocket and pointed it at the middle of our chest and less than fifty centimeters away. Daniel said something no one understood and I, speechless, with my right hand behind my back, managed to reach the latch, turned it, opened the door and we slipped out, ran down the stairs and left. We are still running down Santa Fe Avenue and I swear I will never go to a course by the poet Osvaldo Rossler again.

Paula Winkler

I'm Miss Clueless. As a young woman she was even more clumsy and stubborn. One of my first important cases as a lawyer involved patents and trademarks. As I was embarrassed to ask some older colleague for the address of the national office to find out a couple of things —Google didn't exist then—, I pretended not to and told one of the employees at the reception desk of the consultancy where I worked that I wrote down where to go on a piece of paper because I was in a hurry… I went: it was another consultant, a very well-known one. When I realized the paper (when I got off the elevator "she had sent me" alone), I fled terrified inventing I don't know what nonsense. I was not paralyzed (because I was stubborn), I went into a nearby bar, asked for a phone book and finally found the Patent and Trademark Office. As one of the receptionists had recognized me from the faculty, the anecdote circulated for a long time… Luckily I won the case.

Another: my family, a friend and I are at bus stop 16 in Punta del Este. Sunbathing, don't tell me why, I seem to recognize a well-known French actor. I tell my husband "here I go, I'll ask for an autograph" (there were no cell phones then) and, to his astonishment and my friend's perplexity, I start an impromptu conversation in French, fascinated by the casual encounter. I congratulate him on his performance with Romy Schneider. But he answers me (in French): "Good morning, Paula, I'm so-and-so, we studied Inheritance and Procedural II together, didn't you remember me?" Etc and laughs.

And another: I walk with my son-in-law (being older), afraid of getting lost in a copious Swedish forest by the sea. We talk (in English), and I push my grandson's stroller concentrating on the beach near Stora Essingen and a pier that could work as a landmark… My grandson sings happily, I talk and talk. And suddenly, my son-in-law suggests that he return to English in the face of my long soliloquy in Spanish (a language that he does not understand), even demanding rapid responses from him...

Aldo Louis Novelli

Ridiculous situations, thousands or more, but I can't count most of them because memory is wise and gave them away to oblivion. Of those I remember, there is one from when I was hunting big game, that was a long time ago. Later, pursued by fervent ecologists and vegans, I decided to dedicate myself to photographic hunting of birds.

Since I try to poeticize everything in life, achieving results that could well be part of ridiculous situations, I leave you the poem that recounts said situation.

Grace Perosio

She rings the phone and I answer. A strict voice asks if I am the coordinator of the writing workshop. When I affirm, she asks me how she goes about sending me the texts that she needs to fix.

“No, sir, I don't work that way. I don't do proofreading.

She is surprised, she makes an allusion to the fact that it is a workshop… she thought —she told me something like that— that it was similar to taking a car to the bodyworker.

—It happens to her — she tells me — that I have won many prizes. The last one, from the Rotary Club of Rosario. But they always give me the second or the third. I want to win the first one and if you…

—If I fix the writing for you, I win the prize, not you. It's about learning.

Not very willingly we ended up arranging an interview. The man, in his sixties, tells of an unfortunate sentimental situation. A long courtship interrupted by the death of the woman. And this duel appears repeatedly in his writing. In the end, too delicate. When talking about the work on what is written, I find little reading of well-known writers. Rather, he is a person who attends groups that are organized like clubs, with a lot of social and emotional support, but where he hardly criticizes or frequents literature of different origins. On the other hand, they read a lot among the attendees to accompany each other, a not insignificant goal in this crude and violent society.

But, to add to the complication, Anselmo, as the aspiring poet is called, forces himself to write sonnets. "And I can't even count the syllables, they're not all eleven, you see?"

—It's that counting the syllables is a later help, first you have to have that music inside. Maybe the sonnet is not your thing.

#swimming How to Remove Water from Ears - Part 1 - Using Home Treatments - http://t.co/VGU0MPA5Iw http://t.co/Dn5KwlsUzD

— Swimming HQ Sat Oct 03 05:51:43 +0000 2015

Oh no, don't tell me that. I'm not fit to give up.

—I propose, then, two or three classes, in which you will only come to listen, without writing anything or commenting on anything.

As you can imagine, I have made a selection of notable sonnets from Garcilaso to here. Two weeks passed with their corresponding classes and the third arrived. He knocks on the door. I open it and see him come with a furious face and a huge suitcase, shaped like a chest and quite heavy.

He passes by and asks my permission to place the tome on the table. "This is for you," he says, furious. “Here I bring you all these scams that have been done to me. Pum!, bom!, plaf!”, the metal sounds on the table and the medals, statuettes, plaques and others fall, among ribbons and diplomas.

—I already realized that my verses do not deserve any of this. You don't need to keep reading me. Simply, I was scammed and I was very gullible.

"No, you can't know that." Sit down please. Look, in this type of contest it is about encouraging the enthusiasm of the participants and generally the jury is not allowed to declare the prize void. So it is possible that what you presented was better than what others presented. The issue is with what other scriptures do we continue to compare ourselves afterwards. If we compare ourselves with Borges and yes, we are all far away... Neither one extreme nor the other, is what I recommend to start writing and see if you are really excited about doing the necessary work to improve it.

-I'll think about it. For now, I'm not ready to answer you. But I thank you for allowing me to realize the truth.

I never heard from him again. But I was reassured that, finally, he left in peace and without disrespecting the story of his loss that he was still crying, which was, I think, what worried me the most from the beginning. He wanted to honor her with the first prize! It was obvious.

Carlos Maria Romero Sosa

I don't know, sometimes I think, benevolent towards me, that my shyness has been something like an antidote to ridicule. But perhaps for many there should be nothing more ridiculous than a shy person who, because he is, usually has clumsy gestures.

Ines Legarreta

I think this anecdote qualifies. In 1997 my book of short stories, his second wish, had been published and, among others, it had received a very positive review in the magazine El Planeta Urbano. It hadn't been long since El Planeta Urbano had joined the publishing world, but from the first issue it was clear where the magazine was heading: risk, unconventional approaches in articles and interviews, notes signed by renowned writers or artists; modernity in the design and a great photographic and advertising display that was clearly manifested from the covers, all with celebrities in irreverent compositions. So when the newsroom called me for a job interview, I was flattered and a little uneasy at the same time. What would they offer me? I traveled from Chivilcoy to Buenos Aires and went to the publishing house that was in the Belgrano neighborhood; I was received there by Elsa Drucaroff (he made notes on books), Sergio Varela (he was section editor) and someone else, but I don't remember who; greetings, introductions (we didn't know each other personally until that moment) and after an informal chat about the situation, Sergio Varela told me more or less this: “Well, Inés, since we are interested in your writing, we wanted to invite you to collaborate with some notes and articles as they are given; we like to propose different things and that is why we thought of you for a note on the Golem”. He said "Golem" and looked at me with an amused and expectant face. “Ah, the Golem”, and I immediately began to search from where to approach the subject: Borges, without a doubt, Borges's poem and the heritage of Jewish culture, the meaning of that creation. I guess I was saying it out loud because I was interrupted, "Ummm... no, you heard wrong, not Golem but Golden, the Golden of Esmeralda Street." Silence. Me: "And what is the Golden on Esmeralda Street?" "A bowling alley with male strippers, unique and exclusive for women." Ahhhhh. laughter I had no idea of its existence. "You dare?". "Obviously," I replied. We agreed conditions and I went with two friends; we had a lot of fun and the note came out perfectly (“Golden boys”, in the April 1998 issue of El Planeta Urbano).

Daniel Barroso

It was April 1983 and Raúl Clemente “El Comandante Roque” Yager had been killed. We organized ourselves, a few days later, to make an interference of Channel 11 at a time of good audience.

Each one would take charge of a part of the team (basically in case one fell, that the whole team would not fall). The first to arrive was me who would start assembling the antenna and testing the battery, then the remaining two with the transmitter, the cassette, cables and other connectivity.

When we were already inside the house, in the neighborhood of Villa Pueyrredón, with everything being prepared, the doorbell rings and Marisa (the housewife) looks at us paralyzed with a panicked face.

"I'll pay attention," I told him dryly.

-My in-laws! She," she managed to say between gasps.

They all looked at each other in unison and began to put everything they had brought wherever they could. “From now on we have to improvise”, said one of us and we all agreed. “But what can three unknown guys improvise at the daughter-in-law's house when the husband's away?” I said, bouncing drums from the undercounter to the bathroom and back again.

"I'm coming down," he intoned, almost in a lament, whom we will call Marisa.

The arrival of Marisa's in-laws found us sitting around the dining room table, talking about how difficult it was to hunt ostriches at this time of year. Almost tripping, we got up to greet the “silver wedding”-looking couple, whom we greeted by shaking hands, but with our bodies (from the waist up) twisted towards Marisa, making it impossible to walk without knocking over chairs or getting distended of the sciatic nerve. The smile of the three of us was a grimace between Chaplinesque and mental handicap, while we piled up as if making a barrier to withstand a shot from a free kick by Panadero Díaz.

"Well, tell (suppose) Orlando that we'll see each other when he gets back, that way we'll arrange the trip to San Pedro," one of us said listlessly.

"That's right, the tents are already insured," remarked, almost inaudibly, (let's say) Benjamin.

"It was a pleasure," I said, as we shook hands again at a Laurel and Hardy intersection.

Marisa accompanied us to the door, she said goodbye to us almost screaming, she did not stop sighing, in reality she was on the verge of collapsing due to anguish.

Luckily, the in-laws left right away. They had brought "the dessert that Orlando likes" for when he returned from his work assignment in the south. Recklessly, the interference operation was done the same, a while later and a couple of phone calls in between, treated as wrong by the partner. The short wait time was at a nearby bar with a telephone. Some of the patrons stared in amazement at three lunatics who came in separately, seated at different tables, and giggled non-stop.

susana cella

It is a sad anecdote, and I say sad because of the academic misery that we have had to suffer. As a result of a contest to fill a position as a full professor, one of the jurors was attacked on the networks. She told me this colleague: “They have given me the nickname of Jelinek”. I, in my supine ignorance of what is circulating, said to this dear friend: "Well, at least they have compared you to a Nobel Prize." In my mind was the name of Elfriede Jelinek, the Austrian writer and activist who won that distinction in 2004. My friend contrasted me with the reality of the eunuchs who insulted her. “No”, she told me listening to my ignorance. “They compare me to Olga Karina Jelinek”, and that's when I learned of the misery of the attack. They paired her with a star who was exhibiting in Dancing for a Dream and things like that. I was left with the bitter memory of having read a novel by Elfriede and knowing that she had the same surname as that model.

Rogelio Ramos Signes

I always had the habit of making very brief introductions before reading a poem in a recital; not to explain something (there is nothing to explain) but to break the mood of the previous poem and start again. My reading companions did the same thing for many years: Maísi Colombo, Ricardo Gandolfo and Manuel Martínez Novillo.

Once, during a reading in front of an incredibly crowded audience, a lady who was sitting next to the poet Fátima Gatti told her in a confessional tone: “I like what they say before each poem much more than the poems themselves.”

Ha ha ha. Total failure!

adriana magio

She was studying the Teaching of Spanish and Literature at the Joaquín V. González. She was about nineteen shy and hypersensitive years old. The Faculty was on Avenida de Mayo and San José, in an old building, which is now a hotel. The stairs were marble and worn from many years. I was going down the stairs, with my tight skirt, to the knee, and my thin high heels. In the opposite direction, I saw two young boys coming up, whose appearance made me seriously nervous. My thin heels slipped on the step, and I landed on my tail with my legs open and one of the young men between them: the skirt went up to the crotch, and my thighs were exposed, decorated with the ineffable garter belt that was used at that time, to hold nylon stockings. I know the young man helped me up, but how I got out of there and when I got back on the ground remains a mystery. The huge bruise that lodged in my buttocks took much longer to disappear than my embarrassment.

Alexander Margulis

There was a boy who was going to set up a restaurant on the corner of the house, which overlooks an avenue with heavy and fast traffic where no business operates. I like to paint and I wanted to sell a painting. My argument for him buying me a work made especially for him was that, in this way, with paintings like that, he was going to make his bowling alley a reference site, and that way the clients were going to get to know him for his decoration, as it was too out of the way. The boy gave me a crooked look when I said that. To convince him of my proposal, I offered to test him, taking advantage of the fact that they were still renovating the place and that the acrylics where the previous owner had placed gigantographs of hamburgers were now empty. I would paint one of the acrylics and he would see how it turned out later. He reluctantly agreed. So that Yom Kippur, instead of going to share the celebration with my family, I stayed at home and during the night I copied, from an image that I found browsing on the computer, some immense beaches. I painted the picture with a special acrylic. And I titled it Nice. When I finished it I went to call the boy from the restaurant, I insisted that he come home to see it and I even agreed to correct some details when I discovered the disinterest in his face. The next day I took it finished to the restaurant; As the lack of interest continued, I suggested that he leave it exposed for the whole weekend so that the painting could defend itself. "Hang it up and we'll see what reaction it gets," I said. I spent a weekend at peace with myself, satisfied that I had done my duty as an artist, or with what I thought should be the way to behave as an artist. When I passed the restaurant early Monday, the Formica tables had been covered with floor-length purple tablecloths, matching napkins, and artificial flower centerpieces. It was terribly hot and he was on the corner handing out flyers for the new restaurant, he was sweating inside a smart black suit and his feet were cramped by shiny leather shoes, but he didn't seem to feel uncomfortable being the only one dressed in such a way. on that avenue where none of the private cars, truck drivers and taxi drivers stopped now that the hamburger restaurant was no longer in the way. I was moved by his strength and dignity in the face of imminent failure. And I congratulated myself for having contributed to his dream of the perfect, fine restaurant in the worst place in town. I approached him to ask him about the comments he had obtained regarding the painting. “Didn't like it,” he said. “How did you not like it? Who didn't like it?" "To my lady." “But what does your art lady understand?” I said. Silence. I realized that I was losing and backed off. "Well, I'll take it then...". “How are you taking it…?” he said and for a moment I thought he had come to his senses. "If I take it…". “Ah, no… but I need the acrylic…”. I stared at it. And over his shoulder, to the painting on the wall above the box. The truth is that it was beautiful. “You don't understand”, I said then. “You'll need the acrylic, but now it's a paint. A play”, I added shyly. “A work that has a value by itself”. Suddenly there were two of us who were sweating on that corner of the avenue. At that moment the boy said something unexpected: "How much is it worth?" I said a price. “Well”, he said and I thought that I had fallen short with the figure. "I buy it to you". So I understood. “What are you going to do with the painting?” I said. "Any. I'm going to wash it and put the acrylic back on,” said the boy. I almost hit him. But I held back. “No… you can't do that…”. I wondered what Van Gogh would have done in a similar situation. What would Picasso have done? “How much does acrylic cost?” I asked. The boy answered with all seriousness a figure. It was double what I had said. I thought that my painting was listed on the market, or that this must be the famous art market. "I'll buy you the acrylic," I said. He accepted right away. From that moment on, Nice became the painting par excellence in the living room at home.

Martha Braier

In the middle of the 1970s, on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the death of Ricardo Güiraldes, the director of the Cultural Supplement of the newspaper Clarín at that time, Fernando Alonso, entrusted me with a phone call to Borges, so that our revered writer would honor him with some anecdote or I remember the author of Don Segundo Sombra. I was working on literary reviews for the Supplement and enthusiastically accepted the honorary assignment.

He had to call Borges at 5:00 p.m. sharp at his house and bring a brief note the next day. The thing is that I, with the phone number they had given me written down on a piece of paper, entered a phone booth at the Otamendi Sanatorium, on Azcuénaga Street, just around the corner from the building where I lived, on Paraguay Street. I didn't have a landline phone (and it wasn't easy to get one).

When the housekeeper who attended me passed me to Borges, I managed to write his story as best I could, shocked by that slow and unique voice, leaning the notebook against the glass wall of the cabin, while a long line of anxious people lined up waiting your turn to use the phone.

In the grip of a growing nervousness, and seeing with concern that the line was growing, I timidly thanked Borges for his collaboration, I hung up and took refuge, avoiding their gazes, in the small chapel of the Sanatorium. I stayed there for a long time in search of shelter. It was a lot for a young girl from Tucumán who had just arrived in Buenos Aires, received as a Professor of Letters. Who was going to believe me?

When I took the anecdote to the newspaper, written with absolute fidelity to the words of the famous author of El Aleph, I found out that Borges had already told it several times and that it had been published. Actually, what stood out, with emphasis, was that Güiraldes had forgotten his guitar one night at his house.

It took me a while to receive the telephone line and I have not forgotten that voice or that moment. It is well worth signing this memory with Borgesian verses: "What does successive time matter if there was a fullness, an ecstasy, an afternoon in it."

Will that cabin still exist?

Francis Roman Perez

One cold morning, in my garden, sadness drenched me. I found a butterfly in agony. I took it in my hands. Thank you, just, he told me he. I leave you my wings, he told me. And he left.

Beatrice Arias

When my eldest son, Esteban, was saved from military service in 1991, we decided to celebrate. No one in the family had done it for one reason or another.

We went to the supermarket with Daniel, my husband, and we bought drinks and various foods to start with a snack and continue with sweets and cold cider for the toast.

When we arrived at the checkout to pay, a man of medium height entered, short gray hair, wearing pants and a jean jacket, who approached the owner (the Galician) from behind and pointed a gun at his ribs. They all remained mute and still at the order of the stranger. But me.

I continued chatting with Daniel as if nothing was happening and I commented on why the ATM didn't charge us and we were leaving. At that moment the clients were depositing the silver on the counter, just like Daniel. I asked him why they did it and he replied: "It's an assault."

Then I realized, I froze and started to shake. We slowly went to the back of the supermarket until the thief left. We packed up the groceries and headed home.

The next day, we went back to buy at the supermarket and the owner charged us for everything we brought. We paid for the celebration twice.

Julio Aranda

Not of the ridiculous order, but curious. It was in 1997 or 1998. They invited Jorge Montesano and me, among others, to a poetry reading and asked us to advance the material we were going to read, which seemed strange to us…; among my poems there was one that alluded to the disappeared. What we did not know was that the reading took place at the headquarters of a downtown building that at that time belonged to the Military Circle. They quoted us a couple of days before and "gently" told me that I shouldn't read that poem because the topic was too trite and blah-blah-blah, and that I shouldn't take it as an act of censorship. To my surprise, Jorge Montesano rebuked the two men who attended us, telling them that “we are not going to allow” them to choose the poems for us, and that if they did not agree to delete our names from the program. The men looked at each other, as if in consultation, and I swear I was afraid that everything would continue to get complicated. Finally, they returned the material to us, pointing out that it was only a suggestion. Corollary: I had the pleasure of reading a poem about the disappeared in a cultural event organized in a building that belonged to the Military Circle.

Susana Szwarc

Certain ridiculous situations happened to me with the titles of the books. For example, when it was not yet printed, I took poems from El ojo de Celán to be photocopied. And the photocopier asked me if the whole book he was writing was set in Ceylon, if he had been there. I did not want to bother and said yes, I was there. I couldn't help it and added that it is a place I go to very often.

Luis Alberto Salvarezza

Ridiculous situations:

In Paris, the Desecures family rented us the apartment where we lived while there. A few days after renting, they invite us to dinner. The dinner developed normally until the moment we were presented with the cheese table. Of which we had to try one or two pieces. The hosts through these, they told us later, check if the guest has been satisfied. With Adriana we tried small pieces, but of a lot of cheeses. Unfortunately, the next day, in Civilization class, they told us that we had to be discreet on those occasions. We went and apologized and they laughed a lot. The explanation we gave was naive but valid: that we did not know many of those cheeses, an answer that they found sympathetic.

The first time they asked me what was funny about him: I was looking at the one who asked me. A piece of paper

I commit ridicule permanently in the face of technological advances. I remember taps with sensors and my annoyance: there is no water. Magnetic cards to open doors.

Play popular by misusing popular sayings and making the audience laugh.

Zulema of Artola

I count the most recent ridiculous. I was about to send a WhatsApp message to the new administrator (whom I only know from his photo there) of the building where I live. I inadvertently touched something and instead of the message a sticker came: hearts, little flowers, women's shoes, etc. Of course, then I sent him another message, acknowledging my mistake (so far, no reply).

Claudio F. Portiglia

I lived between ridiculous situations —not all of them publishable—, but one was recorded and alerted me.

I have been writing for as long as I can remember. In an economy of extreme scarcity, the toys that always accompanied me were a notebook and a pencil. Sometimes, too, a box of colored pencils; but I soon realized that I was spending them instead of investing them.

The point is that I spent hours pointing I don't know what. Alone, usually; or with a neighbor To the old question that adults ask about “what do you want to be when you grow up”, I answered that I wanted to write. My mother fantasized about being a scribe, because literature and poetry were foreign to my nuclear family.

Already in high school and with a scholarship from an institution that glimpsed my vocation as a journalist, I was recommended to “practice” in one of the newspapers in the city of Junín. At that time, the most modest and also evening, which had been founded by a recognized radical leader and barely survived.

My first task was to copy the news from the newspaper La Razón from the previous afternoon or from the local morning paper, and “fix” them in such a way that they did not seem copied. Then he went to the police stations in search of the police that accredited the telegrams and, later, he went through the municipal press office to collect communications.

Until the electoral campaign arrived, once Lieutenant General Lanusse, de facto president, lifted the ban, and I had to cover all the acts of "Cámpora al Gobierno, Perón al Poder" that took place in the neighborhoods of my city .

It was a promotion, of course. But here's the ridiculous:

Not only did they never pay me a penny for the many notes I wrote, but in order to read myself in print I had to buy the copy, because they didn't give it to me either. And he bought them, of course. Because the vanity and pride of "writing for the newspaper" were stronger than the conscience of exploitation.

And that my notes were not even signed. Only I knew who the author was. Just me with my intellectual onanism of a fifteen year old boy.

Laura Szwarc

Ridiculous situations have happened to me with the heteronym An Lu with which I sign my poetry. For example, they tell me about An Lu and even crazy stories about her, unaware that it is the same Laura Szwarc. But, are we the same every time? Here we see once again how identity moves.

Paul Ingberg

Touring the Peloponnese in a rented car, we arrived at an accommodation in Nafplio. Between my stammering of modern Greek and the owner's English, I ask her where there is a supermarket to buy what to make us dinner. There are two, a small one nearby and a large one a little further away, they close in a few minutes. Let's go quickly in the car to look for the big one. At a corner we don't know whether to go straight or turn. In the same mix of babble, I ask a guy walking the dog. This one stammers a little more English. He tells me that there is a little on that side. No little, I tell him, I want a big, a big one. Yes, yes, big, over there, a little. Again: me: no little; him: no little, yes big, little, over there. There was no time, the die was cast: we turned where he told us to. In a minute we arrived, just in time, at a huge Lidl supermarket: a German chain, unknown to me until then, which I later rediscovered in many other places. Maybe the guy still remembers that deaf he understood little when he clearly said Lidl.

Anne Guillot

The one that comes to mind has to do with my first book. Already received in the career of Letters, already a secondary and university teacher, I intend to open a literary workshop. Shortly after, I see an ad from dear Gloria Pampillo offering a summer workshop to learn how to coordinate. And there I went. The first surprise was that she very seriously told us: “No one can coordinate a writing workshop if they don't write as well”. And there she had us: the whole summer writing different slogans and, therefore, learning the technique. Also readings, etc. It was a great experience, but I had not gone to write. I feel that the race inhibits. It's something like: what can I write after having read such teachers?

However, I wrote. And she started to get me excited. And I had my first book. Then he gave me the phone number of the ineffable editor José Luis Mangieri. No mail, less text messages, less WhatsApp. Nothing existed: telephone. Many years ago of this.

Appointment with Mangieri, coffee, chat, delivery of the manuscript. "I'll call you in a few days," he says. “Come on”, I reply, nervous. And so I continued… for more than a month (much more). Sure, it must be a disaster; Of course, how could he like my poetry? Of course, what a piece of paper.

One day I gather courage and call him: “Baby, luckily you called. I'm going to post you. But again leave me, even if it's a fact. You didn't put a phone number or address or anything…”. In short: self-boycott… or Cinderella's stepsisters (who, obviously, also live inside me) plotting against me. This is how Curva de mujer was born and here we are.

Carlos Enrique Berbeglia

Yes, one worthy of note, many years ago, in the month of January, on the banks of the Cosquín River, in the province of Córdoba. I was in a camp, with my fellow university students from the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters, when a night storm broke out that caused the river to go out of its bed. The next morning the waters had already returned to the usual bed, although puddles remained in some hollows.

In one of those puddles, which was emptying because the waters were dispersing, there was a small fish the size of a finger that was struggling, desperate, because the element where it survived was running out.

I proceeded to put it between my hands in a bowl with some water and deposit it in the river itself, where it would no longer be at risk of suffocation...

Not to believe! Instead of moving away into the river, he stayed for a long time spinning between my fingers, from the moment I did not take my hand out of the water, as if thanking me for having saved his life, he brushed them over and over again and only moved away when I withdraw my hand from the waters.

If that attitude was not conscious, tell it to the crowd of those who still have the luxury of ignoring the existence of an animal mind, more valuable than that of politicians, economists, judges or corrupt soldiers who keep humanity in the sorry state we know him!

Angela Gentile

You ask if I could tell about some ridiculous situation and thinking of someone from literature, what happened to me with Umberto Eco came to mind.

I traveled from the city of La Plata to Buenos Aires, sent by the Instituto de Cultura Itálica, whose deputy director at that time was Haydée Bencini, director of the Caffé Ristretto program, which was broadcast by Radio Universidad, and of the magazine Dall'Italia 2000. I went with two recorders. I managed to get to Echo (behind the theater stage) and the conference was just beginning, so I remained absolutely silent until it was over and I was able to ask him a few questions. They all wanted to talk to him, of course. But I had forgotten to activate the recorder, where I had to record his greeting for Radio Universidad de La Plata. So I kept calling him: “Master, master, my scusa!” He turns around and tells me: “Un'altra volta Lei!” He laughs and gestures me to come closer. I explained to him that he had forgotten to ask for the greeting for the radio and he does it very well prepared. Then he autographed Opera aperta for me, he wrote me his postal address (because he had told him about an adaptation he had made of Le lenti di fra Guglielmo to use in my classes) and he told me: “Mi scriva! voglio leggerlo!”. And on January 21 he sent me a letter with the answer.

Marcelo Dughetti

In 1997 I had been invited to coordinate a poetry workshop in a prison. It was a day where diverse artistic expressions would converge in workshops for the inmates. With tremendous fear of committing clumsiness in which I improve day by day, I went by bicycle to the prison. I was accompanied by a funny dog that always waited for me at the door of the house and electric shocks from an incipient storm that wrinkled the snout of the most painted. The prison is like an ominous and, of course, oppressive ship, stranded on the outskirts of my city. The guards opened the doors and closed them too: I hate the sound of doors closing. More or less, a forty-minute workshop was calculated that, combined with the other painting, craft, music and model making workshops, would delight the men and women deprived of their liberty. A municipal band would close the event that would perform some of the most influential songs in the gringa pampa: for example, "Who has drunk all the wine?", by Carlos "La Mona" Giménez. In principle, there was no one from the school to receive me, no one from the prison library, none of the directors. Pensé que los oficiales o personal subalterno estarían enterados, pero no.

Nuestra cárcel es un cuadro cerrado con torres de control, pero que vista desde arriba semeja una torre de departamentos, desde luego, a lo Dante, como un averno invertido. Bueno, para sintetizar, tampoco llegaron los otros talleristas y la cosa se puso heavy. Aparecieron las autoridades, el director ordenó continuar con los talleres que ahora se habían reducido sólo a uno y que por la afluencia de personas se haría en la capilla abandonada del penal. Público cautivo, nunca mejor dicho. Yo nunca había tenido tanta concurrencia en un taller. Pusieron hombres de un lado, mujeres del otro y guardias hasta los dientes. En ese contexto la poesía no quería salir de su cueva ni que le pegaran palos. El taller derivó en una charla, y en una charla entre un pichi que al lado de los internos era un niño de cinco años, personas repletas de experiencias de vida dura y traumática. Finalizando la charla fue el desastre, el sumun de mi torpeza, porque animado por el contexto de capilla y recordando lo que decía un viejo cura, se me dio por decir: “Bueno, gente, pueden ir en paz, los dejo libres”. Todos se largaron a reír a carcajadas por la frase y la contestación de una de las reclusas: “Debés ser el único que nos deja libres”. Las risotadas fueron como un coro de ángeles que, como una atmósfera, redujo presión y hasta los más fieros guardias esbozaron una sonrisa por la ocurrencia del peor tallerista que jamás hubiera pisado el infierno.

Norma Etcheverry

En un número del año 2010 de Facundo, aquella buena revista dirigida por escritores de Rosario, salió un dossier titulado “La Plata de los poetas”. No tenía que ver con el dinero, claro, sino con los poetas de nuestra ciudad capital, La Plata. El dossier incluía sendas entrevistas a Néstor Mux, a César Cantoni, ya Gustavo Caso Rosendi, y se plasmó en casa de este último a instancias de Sebastián Riestra. Recuerdo que esa noche fui invitada pero no pude ir, y ellos, generosos, me incluyeron a su manera: en un apartado titulado “La hermandad de la uva” se mencionaba que algunos poetas platenses se juntaban para compartir libros, lecturas, y también botellas de vino tinto. Y en esas líneas dejaban sentado que la tertulia no era exclusivamente masculina, sino que solía acompañarlos la que suscribe. Recuerdo que me agradó esa forma tan particular de tenerme en cuenta, casi de igual a igual si lo medía con la vara de género, aunque consciente de que el mérito me acercaba peligrosamente al borde de una condición etílica no tan feliz, pero exquisitamente valorada si tenemos en cuenta aquel dicho que le adjudican a Horacio: “No sobrevivirán los versos escritos por bebedores de agua”. Aún guardaba en mi memoria otra anécdota que también tiene su origen en el vino, pero ocurrida muchos años antes. En aquella ocasión fue Néstor Mux quien me había invitado a casa de José María Pallaoro, a quien yo no conocía, “a comer unas empanadas y hablar de poesía”, me dijo, por lo cual me pareció atinado llegar con un presente y qué mejor que una botella de vino. Confieso que entonces no sabía de vinos y compré de pasada una marca que me avergüenza nombrar. Cuando entré a la casa lo primero que vi fue una bodeguita preciosa con un montón de botellas de buen nombre, empezando por el modesto y noble López, que suele revocar más de una cuenta. Luego, me pregunté qué pensaría el dueño de casa de mí, y sólo había dos opciones: o yo no sabía nada de vinos o era muy borracha… no sé qué era mejor. Pero, habiendo pasado los años y también los ríos de tinta y los de vino, ese gesto de los “varones de la poesía” en la revista Facundo resultó para mí como cancelar una deuda íntima, puesto que esa amable inclusión saldaba mi ignorancia y me restituía la magia de que el vino es parte de la poesía, como ya sabrían los griegos y particularmente Horacio.

Luis Colombini

Estando en el inicio de la preparación de una obra de teatro, donde se lee primeramente el texto entre todo el grupo, y estando todos sentados alrededor de una mesa, encuentro en uno de los bolsillos de mi abrigo la manivela plástica para levantar el vidrio del Dodge 1500 que yo tenía en esa época. No sé por qué motivo (concentración, expectativa desmedida), me encontré mordiendo la parte giratoria y haciendo girar lentamente la manivela sin tener presente que soy un hombre de barba y bigote. Al tercer giro empecé a notar que el labio superior empezaba a estirarse y el dolor a tornarse un poco inaguantable. Entonces pensé que los giros iniciales habían sido en el sentido opuesto a la dirección de las agujas del reloj; “sabiamente” me dije: ahora vamos a darle en el sentido del reloj. A todo esto, sólo se escuchaban las voces de los actores leyendo el texto. Comencé a transpirar, el dolor, inaguantable, y yo como un idiota con un remolino de pelos atorando la manivela del Dodge 1500. No tuve más remedio que pegar un grito de auxilio. Escena 1: Todos mirándome con el artefacto colgando de mi cara. Escena 2: Yo corriendo buscando una tijera que me aliviara.

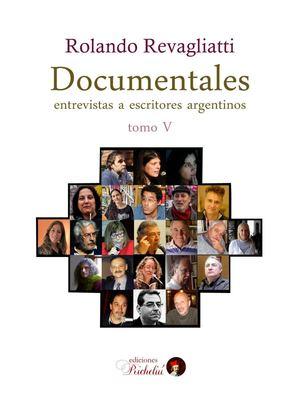

Rolando RevagliattiDocente, psicoanalista y escritor argentino (Buenos Aires, 1945). Su quehacer en narrativa y en poesía ha sido traducido y difundido al francés, vascuence, neerlandés, ruso, italiano, asturiano, alemán, albanés, catalán, inglés, esperanto, portugués, bengalí, maltés, rumano, polaco y búlgaro. Uno de sus poemarios, Ardua, ha sido editado bilingüe castellano-neerlandés, en quinta edición y con traducción del poeta belga Fa Claes, en Apeldoorn, Holanda, 2006, a través del sello Stanza. Ha sido incluido en antologías de la Argentina, Brasil, Perú, México, Chile, Panamá, Estados Unidos, República Dominicana, Venezuela, España, Alemania, Austria, Italia y la India. Ha obtenido premios y menciones en certámenes de poesía de su país y del extranjero. Fue el editor de las colecciones “Olivari”, “Musas de Olivari” y “Huasi”. Coordinó varios ciclos de poesía y diversos eventos públicos, solo o con otros escritores. Ha sido colaborador en cerca de setecientos periódicos, revistas y colecciones de plaquetas, cuadernos, murales, etc., de la mayoría de los países de América y Europa. En soporte papel ha publicado dos volúmenes con cuentos y relatos: Historietas del amor y Muestra en prosa; uno con su dramaturgia: Las piezas de un teatro; quince poemarios: Obras completas en verso hasta acá, De mi mayor estigma (si mal no me equivoco), Trompifai, Fundido encadenado, Tomavistas, Picado contrapicado, Leo y escribo, Ripio, Desecho e izquierdo, Propaga, Ardua, Pictórica, Sopita, Corona de calor, Del franelero popular. Sus libros han sido editados electrónicamente y se hallan disponibles, por ejemplo, en su página personal. Cuatro poemarios suyos, inéditos en soporte papel, Ojalá que te pise un tranvía llamado Deseo, Infamélica, Viene junto con y Habría de abrir, cuentan con dos ediciones digitales de cada uno: en PDF y en versión Flip (libro Flash). También en ediciones electrónicas se hallan los seis tomos, conformados por 159 entrevistas por él realizadas, del libro Documentales. Entrevistas a escritores argentinos. Fotografía del autor : Flavia Revagliatti Sus textos publicados antes de 2015 70 • 127 • 140 • 164 • 168 • 198 • 202 • 211 • 227 • 247 • 250 • 253 • 266 • 285 • 289 • 294Editorial Letralia: Poética del reflejo. 15 años de Letralia (coautor)Editorial Letralia: Letras adolescentes. 16 años de Letralia (coautor)Editorial Letralia: El extraño caso de los escritos criminales. 17 años de Letralia (coautor)Editorial Letralia: Doble en las rocas. 18 años de Letralia (coautor)Últimas entradas de Rolando Revagliatti (ver todo)Coordenadas: Autores de Argentina • Letralia 377Related Posts

María Gabriela Peraza Sjöstrand: Una muchacha retratando el puerto

Jorge Luis Santos García: “Toda fotografía es una ilusión”

Gala Garrido: “El cuerpo es una biblioteca, es un jardín”

El humor y lo sobrenatural se dan la mano en su novela Cinco camas para un muerto Gladys Ruiz de Azúa Aracama narra las reencarnaciones de un donjuán

Adelaida López López: “Todo lo que afecte al ser humano debe ser erradicado de la faz de la Tierra”

Leave a reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.